I’ve been too sick today to do any proper research, so thought I’d write about detectives who were forced to retire because of disease or infirmity. My illness will not, of course, lead to my retirement (one needs a job for that) but I thought it would be a fun subject for a blog post.

Although the word detective conjures up images of tracking down criminals, laying in wait to catch a thief, or (as did often happen) chasing suspects all over Britain, Europe and the world, we rarely stop to think about the long-term effects of such work on the men who did it.

Being a policeman in nineteenth-century London was tough. Hours were long, weather inclement and clothing often inadequate. One look at the old uniforms at the Metropolitan Police Museum makes those long damp English nights seem all the more chilly.

Detectives had to provide their own clothes and many could not have afforded an extensive wardrobe. Most policemen were worn down physically by years on the beat. Others suffered broken bones or head injuries from violent encounters. An unlucky few were killed in action.

Although the detectives of the Detective Department at Scotland Yard were free from regular beat duty, it seems that they retired for the same reasons as men in uniform. There were several different reasons given (“debility,” “bodily infirmity,” and “ill health”) but all boiled down to the same thing – they were worn out. Of the 23 detectives whose pensions are recorded in the archives, 14 list the reason and all 14 men suffered from physical deterioration.

Obviously, much about the physical stamina of the men depended on lifestyle, diet, constitution, and other hereditary factors. Most had spent years on the job, however, and it is difficult to overlook the physical tax such work had on their bodies. On average each had served between 20 and 30 years on the force, having spent a significant portion of that time in uniform before being promoted to the rank of detective.

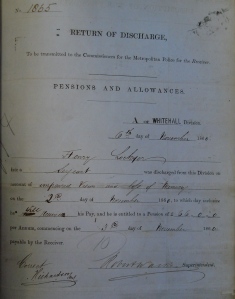

Detective Inspector Henry Locker had lost both his sight and his memory by the time he received a pension in 1860.Superintendent John Haynes retired based on “Injury of the legs and Chronic Rheumatism” in 1856, aged 50. Chief Inspector George Clarke, was released for “age and long service,” (he was 59) in 1878.* Most of the other men were described as suffering from general “ill health.” These totals do not include the men who died while serving and were thus not entitled to pensions. Detective Inspector Davey, for example, died of typhoid while on inquiry in Naples in 1876.

Although policemen are not traditionally considered members of the labouring classes, the physical toll that police work took on many of them is difficult to ignore. Although there is no information on how long these men lived after retirement it is obvious that many would have not have enjoyed good health in their later years.

* Although this is the official statement, George Clarke was implicated in a serious scandal that brought down several senior detectives at Scotland Yard and caused the subsequent reorganization of the Detective Department into the CID. Clarke was the only senior detective found not guilty of perverting the course of justice at the Old Bailey in October 1877.

** This post is the result of independent academic work and is intended for future publication by the author. Please do not reproduce the content of this blog in print or any other media without permission of the author (reblogs excepted). Any questions or concerns can be directed to Rachael Griffin via the Feedback page.

Hi Rachael. I was excited to discover your blog today because some of my historical interests overlap with yours. I couldn’t agree more that the physical demands of the job (for detectives and perhaps more particularly for uniformed officers) were often the causes of early retirement. I would, however, comment on a couple of the examples that you listed. The ‘early’ retirement of my great-great-grandfather, Detective Chief Inspector George Clarke, (after 38 years in the force) was essentially enforced for political reasons (see my blog at http://chrispaynebooks.com/blog/?p=684) . In addition, I think you are mistaken that Whicher died so quickly after leaving the force. Whicher retired from the Metropolitan Police on 19th March 1864 and later worked as a private detective. He was certainly alive and mentioned by newspapers as being in court during the Trial for Perjury of the Tichborne Claimant (e.g. see the Bradford Observer 29 December 1873).

I would like to wish you well with your PhD thesis. If you haven’t already spotted it, I think that you will find that my 2011 book “The Chieftain” (a biography of Detective Inspector George Clarke) could be a source of some information for you and my own blog (http://chrispaynebooks.com/blog) and website (http://chrispaynebooks.com) may contain comments and information of interest. I also have prepared a detailed chronology of George Clarke’s life as a WORD file which I am happy to make available to you if that would be useful.

Best wishes, Chris Payne.

Dear Chris,

Thanks for your interest! You may not remember, but we met several years ago in the Met Archives in Bugsby’s Way while you were researching your book.

I am definitely aware of the role the Turf Fraud Scandal played in your great-great grandfather’s retirement. From what I remember, he was the only senior detective implicated to have escaped conviction at trial. My focus for this blog post, however, is on the reasons listed in the official retirement documents (though the political aspect of DCI Clarke’s retirement certainly features in my thesis).

As for Whicher, the Metropolitan Police Orders indicate that he died in March 1864 after having been ill for several months. I appreciate you bringing this to my attention – I will have to double check the associated facts to sort this conundrum out.

Thanks again and best of luck with your work!

Rachael

Hi Rachael. I remember our meeting at the Met Archives and apologise that I hadn’t made the specific connection to your Blog. I’ve never been terribly good at remembering names. Good to meet you again!

Jonathan Whicher is recorded in Kate Summerscales book (page 276 of the paperback version) to have been on 29th June 1881. The full reference for the book is: Summerscale, K. (2008) The Suspicions of Mr Whicher or The Murder at Road Hill House. Bloomsbury, London (Paperback edition was published in 2009)

Sorry; that last comment should have read…..”Jonathan Whicher’s DEATH is recorded…to have been on 29th June 1881.

Thanks Chris. I’m still curious about who this other Inspector Whicher is…

Best wishes,

Rachael

Afraid that I can’t help much on that front. In ‘The Chieftain’ (page 23), and based on my research, I describe the full complement of the Detective Department in 1862 as being Inspectors Thornton and Whicher, Sergeants Robinson, Williamson, Tanner, Palmer, Alexander Thomson,James Thomson and George Clarke. A further, and temporary inspector position remained unfilled between 1859 and 1864. I’m pretty sure that there wasn’t a second “Inspector Whicher ” in the Detective Department at that time. In my chronological notes from Met Police Orders, I have noted that it was recorded that Whicher visited the Met Police Surgeon-in-Chief on 23 Jan 1863 and 26 Feb 1864, and on 19th March 1864 there is an announcement of his retirement (on the previous day). However, as you know, the Police Orders are pretty detailed and it is quite easy to miss things!

Hi Chris,

I have exactly the same information for Whicher from the Police Orders: Sick leave for 27 October 1862, inspection by the Surgeon-in-Chief on 22 January 1863, extended sick leave on 2 March 1863. Whoever this Whicher was, on 19 March 1864 it states that “Detective Inspector Whicher” was pensioned that that he died on the 21st. Strange coincidence.

Beats me!

Rachael, I am really interested in the physical deterioration of your policemen! I’m thinking about ideas of manliness and it has struck me how much the values of this ideal of masculinity is based upon a healthy, functioning body.

Men whose body was damaged therefore suffered the material consequences of being unable to work full-time etc, but I think that it also undermined their sense of self as a man. They were certainly judged to be less than a man.

I hope I can get back to you to chat about the detectives and their physical impairments when I am writing this bit of my research?

Hi Joanne,

I’d be happy to chat with you about that. Between now and then, I’ll see if I can rustle up some of the literature on the arduous work of policing.

Looking forward to chatting with you,

Rachael